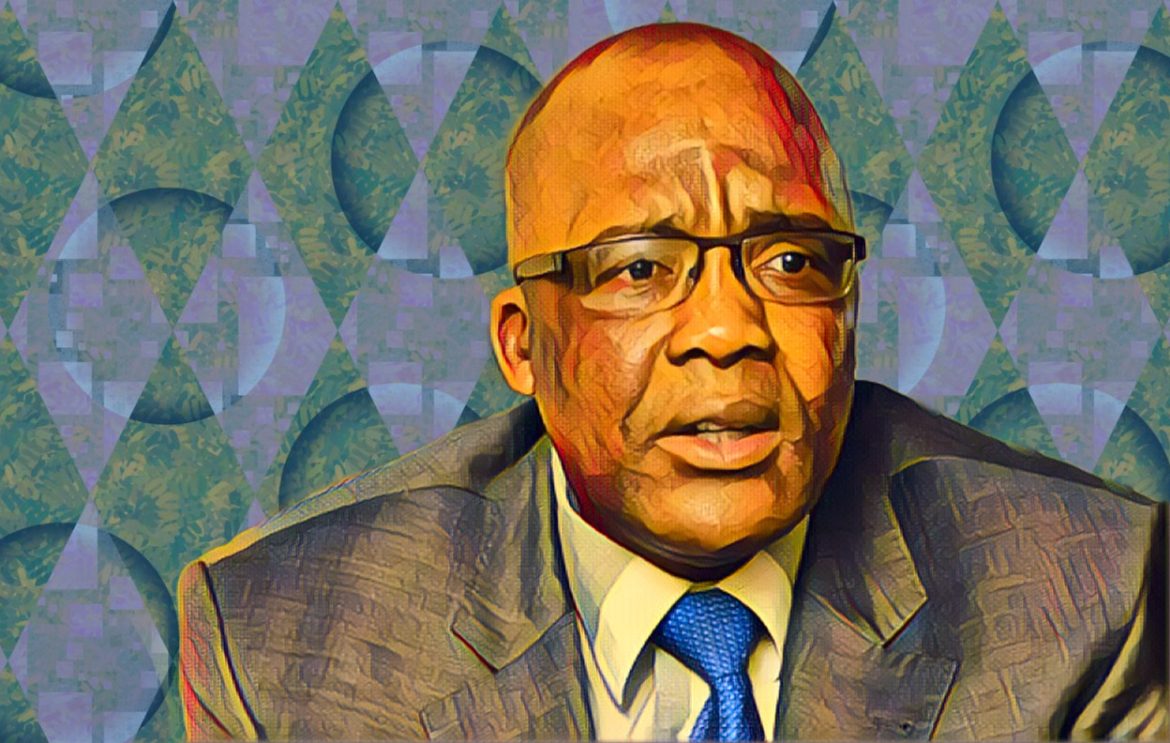

South Africa’s Health Minister, Aaron Motsoaledi, has sharply criticized Zimbabwe for allowing its deteriorating health system to burden South African hospitals. Motsoaledi’s remarks underscore growing frustration within South Africa over the influx of Zimbabwean patients, who are seeking treatment due to their country’s struggling healthcare infrastructure.

Zimbabwe’s health system has been in decline for years, with public hospitals often unable to provide even basic medication like painkillers. Despite this, the Zimbabwean government has been spending millions of U.S. dollars on other sectors, neglecting the critical needs of its healthcare system. The resulting shortfall in healthcare services has driven many Zimbabweans to cross the border into South Africa, where they seek the medical care they cannot find at home.

Motsoaledi, who was appointed South Africa’s Health Minister on July 4, did not mince words when addressing the issue during an African National Congress (ANC) national executive committee Lekgotla in Benoni. He likened some African leaders to irresponsible parents who send their children to their neighbors for food without first asking for permission. In his view, Zimbabwe’s leadership is effectively doing the same by allowing its citizens to flood South Africa’s healthcare system without addressing the root causes at home.

“They just close their eyes and let people cross the border into South Africa,” Motsoaledi said. “It’s unfair. And I want to say this publicly, even though it’s a sensitive issue.”

Motsoaledi referenced an incident involving Dr. Phophi Ramathuba, who, as Limpopo’s Health MEC in 2022, criticized Zimbabwean authorities for overburdening South Africa’s health services. Ramathuba had received backlash for her comments at the time, but Motsoaledi defended her stance. He recalled how Ramathuba received a letter from a general practitioner in Zimbabwe asking South African doctors to provide a pint of blood to a Zimbabwean cancer patient who had already reached stage 4.

“In other words, one country asking another country to take on its responsibilities,” Motsoaledi said. “That is abhorrent to me. Blood is not manufactured; we get it from our population. There are human beings in Zimbabwe with blood, lots of it, for that matter.”

He continued by suggesting that Zimbabwe should focus on improving its own healthcare capabilities, including blood donation programs, rather than simply relying on South Africa. “All they need to do, if they don’t have the technology to collect blood, is to come to South Africa and ask for help in setting up blood donation services in their own country,” he said. “Instead, they are closing their eyes and sending their people over the border. It’s unfair.”

Ramathuba, who was elected the first female Premier of Limpopo in June after the ANC won a majority in the provincial legislature, has long been vocal about the strain that Zimbabwe’s health crisis places on South Africa. Her province, being the closest to the Zimbabwean border, bears the brunt of the influx of patients seeking better medical care.

Zimbabwe’s ongoing health crisis has forced many of its citizens to seek treatment in neighboring countries. Limpopo, due to its proximity, has become the primary destination for Zimbabweans in need of healthcare. This has put significant pressure on local hospitals, which are already struggling to meet the needs of South Africans.

Motsoaledi also criticized African leaders for neglecting their national health systems, noting that many of them seek medical treatment abroad rather than investing in their countries’ healthcare infrastructure. “Part of the reason is that heads of state on this continent—and this is the only continent where this happens—when they are sick, they go to other continents and leave their nationals to fend for themselves. We have asked that this practice must stop,” he said.

The late former Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe was a prime example of this phenomenon. Mugabe frequently traveled to Asian countries for medical treatment, making several trips per year during his presidency. He eventually died in September 2019 in Singapore, where he had gone for treatment.

Critics argue that Zimbabwe’s health crisis is primarily due to the government’s underfunding of the sector. The lack of investment has left public hospitals severely under-resourced, leading to an exodus of skilled healthcare professionals who have migrated to other countries in search of better working conditions and opportunities. Development partners and international organizations have stepped in to fill some gaps, but their efforts have not been enough to fully address the systemic issues plaguing Zimbabwe’s healthcare system.