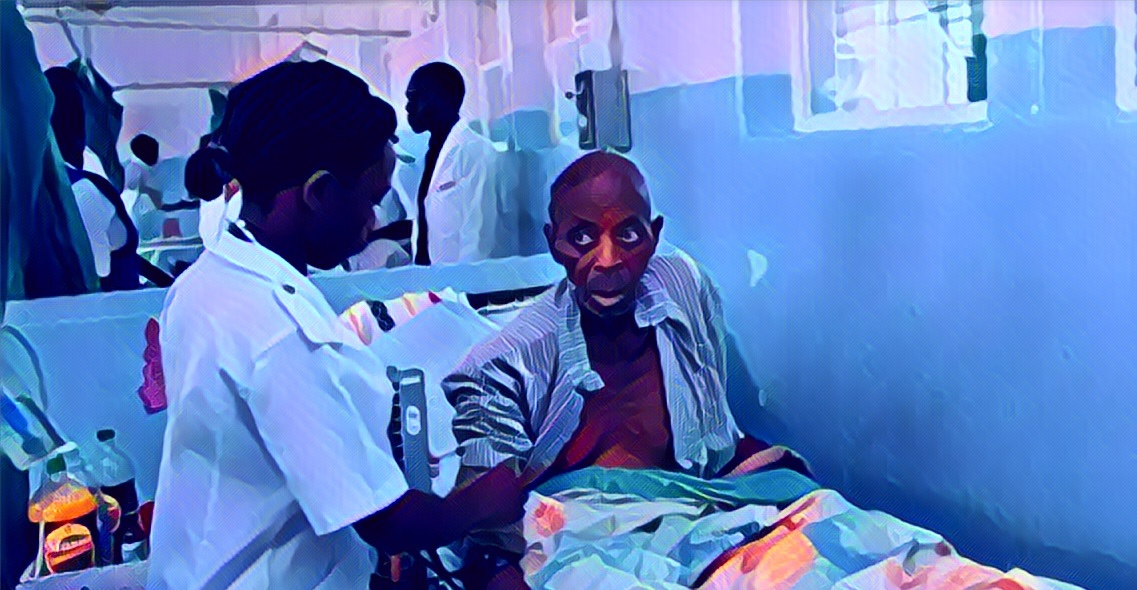

In an exodus driven by economic and political turmoil, health professionals from Zimbabwe are increasingly relocating abroad, seeking better opportunities and working conditions. Despite the geographical distance, many such as Setfree Mafukidze, a former head nurse from Chivu, maintain a strong emotional connection to their patients back home, often providing remote medical consultations and support.

Mafukidze’s story is not unique. In the wake of Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic, the United Kingdom has become a prime destination for skilled health workers from Zimbabwe, with over 21,130 Zimbabweans granted work visas between September 2022 and September 2023—a 169 percent increase from the previous year. This migration is significantly impacting Zimbabwe’s healthcare system, already strained by shortages of staff and resources.

The World Health Organization noted a reduction of at least 4,600 public sector health workers in Zimbabwe since 2019, despite efforts to increase recruitment. The deteriorating conditions in the health sector, coupled with poor pay, have fueled the departure of these essential workers.

Professionals like Mafukidze, who moved to the UK with his family in 2021, find themselves torn between the improved financial and academic opportunities available abroad and the dire healthcare situation back in Zimbabwe. They continue to engage with their former patients, offering advice and support from thousands of miles away. This ongoing connection highlights a significant gap in healthcare provision in Zimbabwe, exacerbated by the economic crisis under President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s administration.

Healthcare workers who have left speak of their struggles with the decision, recognizing the impact their departure has on the communities they served. Many express a desire to return home eventually to contribute to rebuilding the healthcare system, but the current economic instability and poor working conditions deter them.

Zimbabweans living in border towns are now seeking medical care in neighboring countries, further underscoring the healthcare crisis. Meanwhile, those who have relocated to the UK face challenges such as adapting to the weather, experiencing homesickness, and navigating the British healthcare system’s demands.

Despite these challenges, calls for these expatriate health workers to return and help rebuild Zimbabwe’s healthcare system are growing louder. Figures like Professor Solwayo Ngwenya, who returned to Zimbabwe after working in the UK’s National Health Service, serve as an inspiration, demonstrating the potential benefits of returning home.

As the debate continues within the Zimbabwean diaspora about the timing and feasibility of returning, the healthcare workers’ dedication to their homeland remains evident. They are caught in a dilemma between securing a better future for themselves and their families and serving their compatriots in need.